Alma Singer’s Rules For Living

In a profile written by Cannopy Magazine, with humour, colour, and a childlike scrawl, Alma Singer reclaims vulgarity as a tool for survival and truth-telling in the gallery.

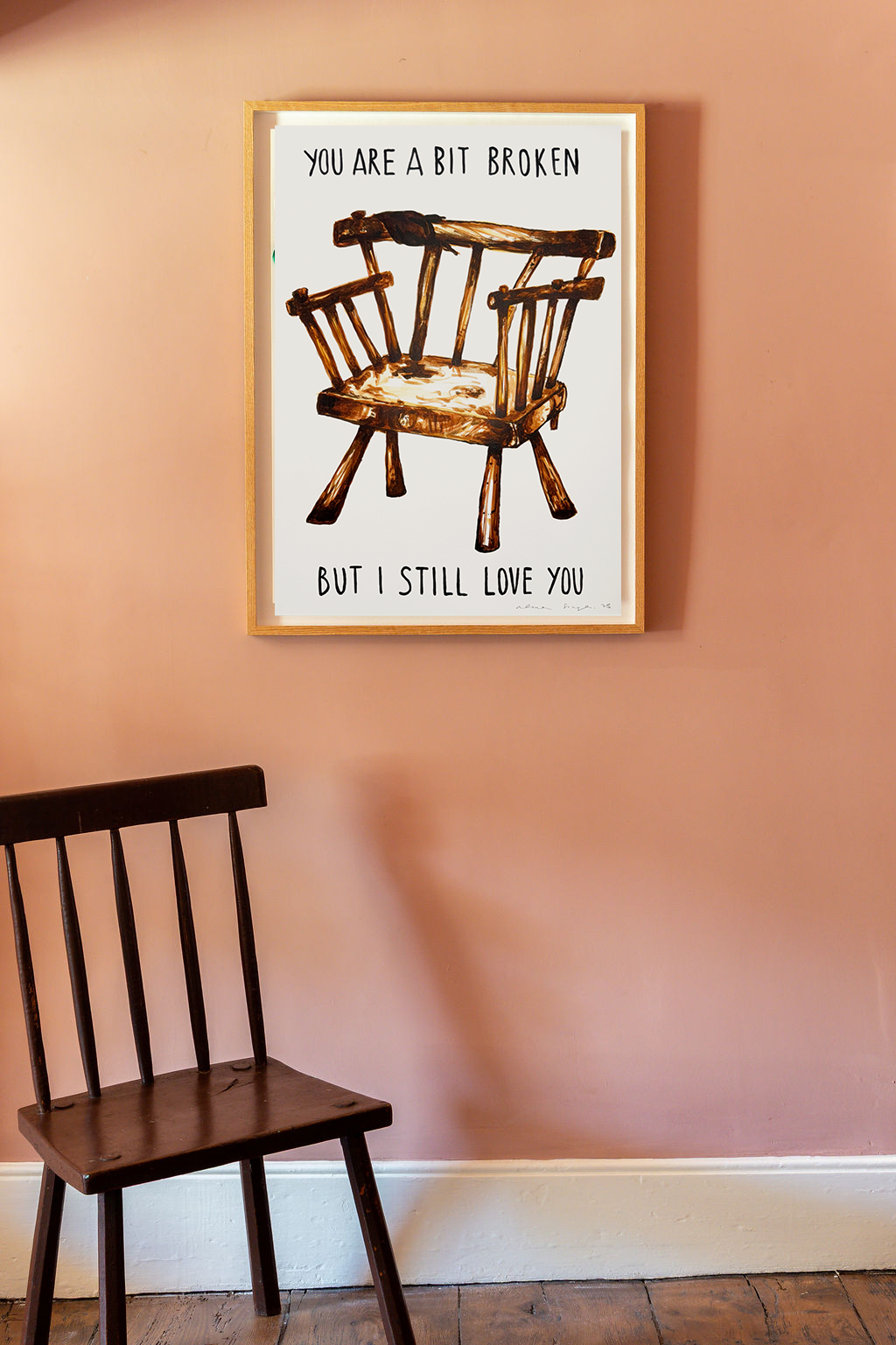

There are no apologies here. Kent-based multidisciplinary artist Alma Singer has built an aesthetic of vulgarity, play, and fonts that refuse to behave. Her work does not simply adorn; it confronts. Her slogans bark back at convention, her naïve lettering slants defiantly, and her humor undercuts the authority of “serious art” with the bluntness of a swear word scrawled across the wall of a kindergarten classroom.

That elementary classroom is, in fact, a recurring echo in her style. Consider HAVING A DICK DOESN’T MEAN YOU HAVE TO BE ONE, a piece rendered in the cheerful alphabet-block style of kindergarten pedagogy. At first glance, it could hang above the chalkboard in a primary school. Step closer and the illusion collapses: innocence turns into indictment. The vulgarity is not incidental but essential, collapsing the distance between childlike aesthetics and adult realities. Her genius lies in that clash; color-drenched, playfulness pressed against raw, lived critique.

No Apologies

It is no coincidence that Singer works under an alias. The act of renaming oneself has a long lineage across the arts. George Eliot, Stephen King, and MF DOOM all created alternate selves to say what their given names could not. A pseudonym signals not retreat but expansion. Carla Nizzola, who creates under the pseudonym Alma Singer, crafts a parallel self who is freer to say, “Back off. This is what I have to say.” The shield of an alias enables the sword of bluntness.

That sword cuts with humour. Her Only Fans installation, staging literal fans for sale in a shop window, and her painting smeared in red ink and stamped with the word “ARTY” both skewer internet culture and the art world’s gatekeeping in one stroke. The gag is funny at first blush, but the layers bite. Arty is one of those words that masquerades as harmless when in fact it belittles, implying something is decorative, unserious, or trying too hard. Singer flips the insult on its head, writing it herself in bold red, near-bloody, refusing to let the word diminish her. The humor is childlike in its pun, but adult in its critique, another reminder that play is not frivolous but urgent.

This is the undercurrent of her entire practice: the necessity of play. Singer’s hand-drawn fonts are deliberately childlike. But the primary school vibes carry weight. Adults, she seems to argue, require play as much as children do; to lose it is to lose yourself. In Singer’s hands, play is not distraction but survival, a radical stance against rigidity. Has someone ever called you “ridiculous” when you’re just being yourself? If so, surely Nizzola can relate.

Why a pseudonym?

That ethos extends to her exhibitions. The walls are painted as if children had been given free rein — flowers, butterflies, and doodles displayed across the surface — while the framed works hang askew, as though crookedly placed by tiny hands. The imperfection is intentional, reminding viewers that looseness and laughter have a place in even the most “serious” of spaces. Perhaps Singer is more forgiving of that need to play than Nizzola. Or perhaps her audience is. What may be dismissed as unserious under Nizzola’s signature becomes, under Singer’s, a demand to listen.

Her studio reveals this push-and-pull between levity and honesty. On one wall, a self-portrait appears as nothing more than a stick figure, humorously reductive. Beneath it, a vase of flowers carries the caption “Sorry I hate you,” similar to her potted plant piece bearing the words “Sorry I killed you.” Together, they distill her knack for mixing comedy with cruelty, tenderness with regret. The flowers recall a friend’s confession, that is, that her husband only ever brought a bouquet of flowers after arguments. The disturbing part was that there were always fresh bouquets in the house. Singer’s humour leans toward hard truths, where laughter softens what would otherwise wound.

Even her resolutions mix earnest discipline with cheek: Paint every day, have more sex, be kinder, more sex, worry less, sex. The repetition is comic, but also telling. Humor becomes a way of acknowledging desire without shame, elevating the ordinary “rules to live by” into a manifesto of messy humanity.

The Studio

Humour and Vulgarity

That humanity extends to Singer’s candid admissions of attraction. One piece, written with primary-colored letters smooshed together like the ABCs on a classroom wall, reads: SOMETIMES I WANT TO KISS GIRLS. At first glance it mimics a child’s learning tool, rendered in the bright hues of a kindergarten palette. But look closer and the innocent styling collapses: the message is not softened, but masked; hidden in plain sight, its candor emboldened by the very format meant to conceal it. What might feel too frightening to say in plain gray and direct terms becomes liberating in color. Here, color is not decoration but permission. Color for Singer is used as a tool to reveal truths that polite society, and perhaps Nizzola herself, might have muted.

Vulgarity sharpens this honesty. Her text pieces, such as “BE YOURSELF UNLESS YOU ARE A DICKHEAD,” or the dog who declares, “I ONLY BARK AT CUNTS,” strip language of its polite varnish. They read like playground taunts, and yet, in their brazenness, they achieve what polite speech cannot: they say exactly what they mean.

Her humor and vulgarity are not masks but amplifiers, the way an alias can be both shield and megaphone. Singer is not less herself under another name; she is more. The pseudonym expands her creative license, and within that expansion comes the freedom to be obscene, hilarious, and unforgiving. Where Nizzola may have been judged, Singer is defiant. Where politeness might have silenced, Singer shouts in block letters. She challenges the hierarchy head-on, suggesting that imperfection, play, and profanity have as much place in a gallery as oil portraits and sculpted bronzes.

The frequent use of profanity in her pieces raises its own question: had Nizzola once been scolded for such language? As Singer, she claims that space back. What might once have been met with reprimand is now broadcast in bold capitals, a playground of her own making. A space where she feels free to have a potty mouth (no soap required) allows her to finally say what she might have wanted to say to the scolder all along: I’m not a child.

Ultimately, Singer’s art operates in tension, between childlike play and adult critique, between vulgarity and sincerity, between the name she was given and the one she chose. What emerges is a practice that insists on honesty, no matter how messy, loud, or profane. She does not ask for permission to speak; she scrawls it in ink, in caps, in fonts that dare you to look away. And while her crooked frames and irreverent slogans may provoke laughter, they are underpinned by flashes of precision: the finely detailed leaves of a plant, or the startling realism in the eyes of the bulldog who only barks at cunts.

These moments remind us that Singer’s humour is deliberate, her play intentional, her vulgarity earned.

Claiming it back

Alma’s work speaks most clearly to the crowd that takes itself far too seriously, that is, artists and tastemakers who guard the borders of legitimacy as if humor and imperfection have no place inside. To them, Singer’s response is simple: fuck off, I’m an artist, too. Don’t be a dickhead.

Words by Kathleen Hokit